The Heroic, the Exceptional and the Day to Day

There is a distinct luminescence that rises from behind the hills in the early morning in Tuscany. Looking east towards the hilltops from any valley the partially clouded sky is lit a glowing orange, as if a giant hand has struck a match in the early morning light. The glow fades slowly, and transcends itself into the orange and gold hues that spill off the hillsides and drip over the edges of the greens and olives that are knitted together so haphazardly, yet offer such a picturesque, elegant and enticing panorama. In the distance, a stone farmhouse, its shades of light brown at once contrasting and blending so neatly into the landscape, sits idly, as it has done so for centuries. While often times views like this are seen in photographs and paintings, the most deliberate vantage point is from the seat of a bicycle. The kaleidoscope of colors, layers and textures combined with the imagination creates one of the most beautiful and enduring landscapes to pursue the simplest of daily pleasures: eating, drinking and cycling.

Riding through the Tuscan countryside consists of all the elements I dream about when imagining the perfect bike ride. Simple and beautiful is the iconography that defines it and heroic is the history behind it: elegant Cyprus trees rising above sloping vineyards, shades of green layered across the undulating horizon. Hidden behind this, are the strade bianche – white roads- that form the backbone of Tuscan life and have been criss crossed for centuries by every form of agricultural entity that has worked the fields in pursuit of a simple and authentic lifestyle. In Italian, Eroica translates to heroic. This word has come to represent the history of cycling in Tuscany through an annual cycling event known simply as L’Eroica. The Heroic. But this is more than a gran fondo, more than an objective, more significant than just a ride to conquer. There is an essence- a feel, a sensation- that is aroused with the first scent of embrocation and upon seeing the visual parade that is l’Eroica.

The small village of Gaiole in Chianti, unchanged for hundreds of years and representative in so many ways of the Tuscany time randomly forgets, is annually transformed into what can only be described as a movie set to host l’Eroica. Hundreds of cyclists, decorated in wool jerseys stitched with the names of local clubs and bike manufacturers, spare tires crossed over their shoulders, fill the cobbled piazza. Some ride thin tube traditional steel bikes, others on more vintage machines dating back to the turn of the 20th century, the hum of chatter filling the cool morning air as small groups begin to collect. A marching band strikes in the distance, while spectators, decorated in wool hats and sweaters, stockings tucked into their balloon woolen pants lean casually on the ornate running boards of the vintage automobiles that frame the cyclists. This is certainly not the Tuscany I am familiar with, or visualize when I close my eyes. As important as it is for l’Eroica to express its identity through these riders and across the strade bianche, it is equally important to consume this for the experience and not strictly for the privilege of an accomplishment. There are many other events that cater to the sportif minded cyclist who wants to tick off prestigious climbs or endure insane distances and crowds for the sake of adding to one’s amateur cycling resume. Riding l’Eroica, whether its 75 kilometers or 202, is much like finding a rare bottle of wine on a wine list. There is the initial surprise, followed by delight. Then sniff, swirl, sip and enjoy. Any other way is to completely fast forward past the sensations that make the event what it is-the preservation of a culturally significant era that is expressed purely through the celebration of the bicycle and the heroes that brought the sport to life.

While Tuscany is widely regarded as the true birthplace of the Italian Renaissance, and has been home to some of the most influential people in the history of arts and science like Michelangelo, Dante and da Vinci, it still remains in many ways a simple, peasant, agricultural land that strives to remain true to this heritage. The most highly regarded cyclist from Tuscany is the legendary Gino Bartali, so devoutly religious he earned the nickname Gino the Pious. His legacy, and that of the Italian influence on the sport through the eyes of the Tuscans, is immortalized at the Gino Bartali museum, a treasure chest of jewels hidden beneath the shadows of Michelangelo’s David and Brunelleschi’s Duomo. By having such an archive, there is a sense of security in keeping the past alive in the minds, faces and actions of the octogenarians, and instilling this simplicity in the minds and hearts of locals and foreigners alike. Devotion to heritage- seen and felt to this day in the Sunday dinners that grace Italian tables-and reveling in the heroic feats accomplished by their brethren was important. In Tuscany this means cycling, and historically this means Bartali, and more significantly, the events of 1948.

After World War II, Bartali returned to race the Tour de France in 1948. It was during this Tour that Palmiro Togliatti, the leader of the Italian communist party, was shot in the neck by a sniper as he was leaving the parliament building. The writer Bernard Chambaz said, “History and myth united, and a miracle if you like, because that evening Bartali got a phone call at his hotel. In a bad mood, dubious, he didn’t want to answer. But someone whispered that it was Alcide de Gasperi, his old friend from Catholic Action, now parliamentary president, who told him that Palmiro Togliatti, secretary-general of the communist party, had been shot at and had survived by a miracle. The situation in the peninsula was very tense amid the ravages of the Cold War. Italy needed Bartali to do what he best knew how to do, to win stages.” Amidst a pending revolt, Bartali proceeded to win three stages in a row and led the Tour by 14 minutes. Another written archive states:

“Just as it seemed the communists would stage a full-scale revolt, a deputy ran into the chamber shouting ‘Bartali’s won the Tour de France!’ All differences were at once forgotten as the feuding politicians applauded and congratulated each other on a cause for such national pride. That day, with immaculate timing, Togliatti awoke from his coma on his hospital bed, inquired how the Tour was going, and recommended calm. All over the country political animosities were for the time being swept aside by the celebrations and a looming crisis was averted. The former prime minister, Giulio Andreotti said: “To say that civil war was averted by a Tour de France victory is surely excessive. But it is undeniable that on that 14th of July of 1948, day of the attack on Togliatti, Bartali contributed to ease the tensions.”

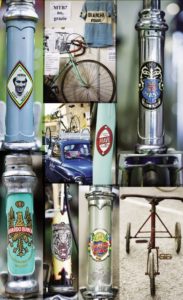

On a bright October afternoon, I stepped onto the small terrace that graces the entrance of the Gino Bartali museum in Ponte A Ema, a stones throw from the Arno River and his birthplace and lifelong home. After waiting 15 minutes, an elderly man shuffled across the terrace from the neighboring bar and unlocked the museum and invited me in. Time, much like traffic signs, is purely symbolic in Italy. For the next two hours, I was the honored guest into the mind and memories of Lorenzo Petronici, a man of 78 who once pedaled his bike through these very streets with Bartali. Often times, when visiting a museum, there is great anticipation of the sensations brought on by a specific piece of art. While I was prepared to see dozens of bikes, what was unexpected was Lorenzo’s narration, his pride and the invitation to view-impossibly-the hundreds of personal photos and original copies of every Gazzetta dello Sport printed from every stage of every Giro d’Italia. Bikes from Bianchi, Legnano, Stucchi and Olympia; jerseys from Bartali’s career with Atala, Bartali-Brooklin, the Tour and the Italian National team; wheels and components from Campagnolo illustrating the development of gear changing devices and the invention of the derailleur. The visual bounty was astounding, but Lorenzo’s passion, his stories, his patience-after all, what was my hurry?-this was the jewel, the missing piece of the puzzle needed to script my personal definition of l’Eroica. Perhaps this was the golden age of cycling I’ve been searching for, suddenly so neatly and elegantly gift wrapped for me from the heart of a man who has lived through exactly what he is working to preserve.

Viewing an historic bike in a museum is equal to hearing an exaggeration- it may peak your interest, but after a bit of time, it just defies plausibility. Similar is the feeling when seeing a vintage wool jersey hanging on a wall, or a faded black and white photo of a rider with his spare tire crossed over his shoulders, the road surface gravel. Encountering a rider who has stepped out from such a photo is an aberration against the contemporary backdrop that we live in. This appears as one frame, the sense that a comic book hero has briefly come to life. A group of two dozen or more, however, placed inside the boundaries of a celebrated landscape, suddenly animates the comic strip, an invitation to stroll across multiple frames, to live inside the black and white photo, the aberration suddenly the rider straddling a contemporary carbon bike with electronic shifters. There is no stopping the demands of modernization, but this is no reason not to celebrate, to indulge in the intricacies of an aura that is brought to life by thousands of Italians embracing their roots and revolving the past into the present.

L’Eroica is purely Tuscan, much like the Colle delle Finestre is Piemontese, the Madonna del Ghisallo is Lombard and the Marmolada is Sud Tyrolean. It becomes iconic not because of what it is, but because of what it represents- a cultural icon that proudly speaks for the people and their lifestyle. Each rider is free to interpret the meaning and importance l’Eroica has on their own legacy, their own Italian heritage. It’s a moving memorial that transcends time, and it’s not the display of the Molteni, Faema or Brooklyn team jerseys that defines the vintage feel- each so well reintroduced into modern bike culture over the past 10 years-but the small local clubs, whose jerseys are decorated with hand stitched lettering announcing the rider’s allegiance: G.S Sillaro; Sanvido; Beppi; Ascolese; red and white; blue and yellow; green and gold; yellow and black. Like the flags of the Italian city states that have marked time over the centuries, these jerseys have a common thread of importance-heritage, dedication and loyalty.

The professional race Monte Paschi Strade Bianche, started in 2007, has drawn comparisons to the northern spring classics, specifically Paris-Roubaix. But this is an undeserving, unwarranted and unfair comparison- not because it is harder, or easier, but because it is different, and because it has its own cultural landscape to draw from. While the cobbled sections of Flanders- the Kerkgate or Haeghoek for instance- and Paris-Roubaix are predominantly flat and relatively straight, the strade bianche of l’Eroica are two things the Northern Classics cobbles are not. The obvious is cobbled, so any comparisons are unfair. The second is hilly. Very hilly. L’Eroica will never match the brutality of the Koppenberg or the mystique of the Muur van Geraardsbergen, but the unique nature of the strade bianche demands it be viewed for what it is. Loose gravel on pitted, lumpy and rutted roads that snake sharply up, then zig zag across, and finally steeply down for up to 15 kilometers at a time, demanding an intense level of physical effort and mental concentration that many riders-especially amateurs- are unprepared for.

The culture it represents is far different than the hellish war torn landscape of Northern France or the bitter, wind swept fields of Flanders. The lifestyle it embraces is not unique, but is a continuation, regardless of whether the race occurs or not. Unlike France or Belgium, the race does not have a grip on the population, so it lacks the pure authenticity that comes with 100+ years of results. This may certainly change, but in a unique twist, it is the race that has developed because of the amateur ride, not the opposite, so the survival of l’Eroica is not based on professional success. In the tenuous business that pro cycling is these days, this is refreshing. There is no iconic sector of gravel, no fabled climb, no single location where the race will be played out. The race could start in Gaiole, or Asciano, or Trequanda. There is an aura, an essence, that exists on all the gravel roads, in either direction, whether it’s included in the race or gran fondo or not. Tractors and cars still access vineyards, fields, farmhouses, churches. Locals collect chestnuts, pick pears and hunt for truffles. The success of l’Eroica is through the expression of this culture as represented by the strade bianche, not because of it. It can be mimicked but it cannot be replicated.

The culture it represents is far different than the hellish war torn landscape of Northern France or the bitter, wind swept fields of Flanders. The lifestyle it embraces is not unique, but is a continuation, regardless of whether the race occurs or not. Unlike France or Belgium, the race does not have a grip on the population, so it lacks the pure authenticity that comes with 100+ years of results. This may certainly change, but in a unique twist, it is the race that has developed because of the amateur ride, not the opposite, so the survival of l’Eroica is not based on professional success. In the tenuous business that pro cycling is these days, this is refreshing. There is no iconic sector of gravel, no fabled climb, no single location where the race will be played out. The race could start in Gaiole, or Asciano, or Trequanda. There is an aura, an essence, that exists on all the gravel roads, in either direction, whether it’s included in the race or gran fondo or not. Tractors and cars still access vineyards, fields, farmhouses, churches. Locals collect chestnuts, pick pears and hunt for truffles. The success of l’Eroica is through the expression of this culture as represented by the strade bianche, not because of it. It can be mimicked but it cannot be replicated.

If you are fortunate enough to stand on a hillside in Tuscany at night, looking across at the flickering lights of the homes and villages, to look skyward on a clear night is to see the brilliant radiance of one of the most timeless wonders of the universe. A star filled sky shimmering like a reflection in still water, a thousand proud eyes staring down at the simplicity of life that fills the hillside. This is Tuscany. This is heroic. This is the exceptional day to day.